Earlier this spring I introduced Linda James—the first woman to enroll and graduate with a Harvard Credential on the same basis as men (Lost and Found, Pt. 1) . Our discovery of Linda’s path, post-Harvard, has come with its fair share of surprises, beginning with a career in immigrant public health before shifting to a difficult yet rewarding life in agriculture and education in the Midwest.

After receiving her C.P.H. from the Harvard-MIT School for Health Officers (now known as the Harvard School of Public Health) in 1917, Linda spent the next four years in various positions in public health administration in Massachusetts and Minnesota. She was a health inspector for Massachusetts Department of Labor and Industry, and a research associate on the health of immigrants in industry for the Carnegie Americanization Study. During this time, Linda attended the Americanization Conference in Washington on May 12-15, 1919, which focused on a congressional bill that outlined a path to Americanization. She also conducted research and prepared materials and statistics on industrial medicine and immigrants for Michael Marks Davis’s publication, Immigrant Health and the Community (New York and London: Harper & Brothers, 1921).

Linda’s professional life shifted in 1922 when she married William A. Benitt, a young attorney from Goodhue, Minnesota. The couple made the collective decision to leave their urban communities and careers to become farmers. From 1929-1930 they both enrolled in the College of Agriculture at the University of Minnesota and, after completing their masters’ degrees, purchased “Apple Acres”—a 200-acre farm in South Washington County, Minnesota. 1930 was a difficult year to begin farming, as it was the start of a decade marked by sagging crop prices and drought. In addition to this hardship, life on Apple Acres during its first decade was very primitive; there was no running water or electricity. Linda and William were also the sole workers on their farm, tending eight hundred apple trees and over one thousand laying hens.

In spite of these hardships, the Benitts were politically active within their community. During the same year of their

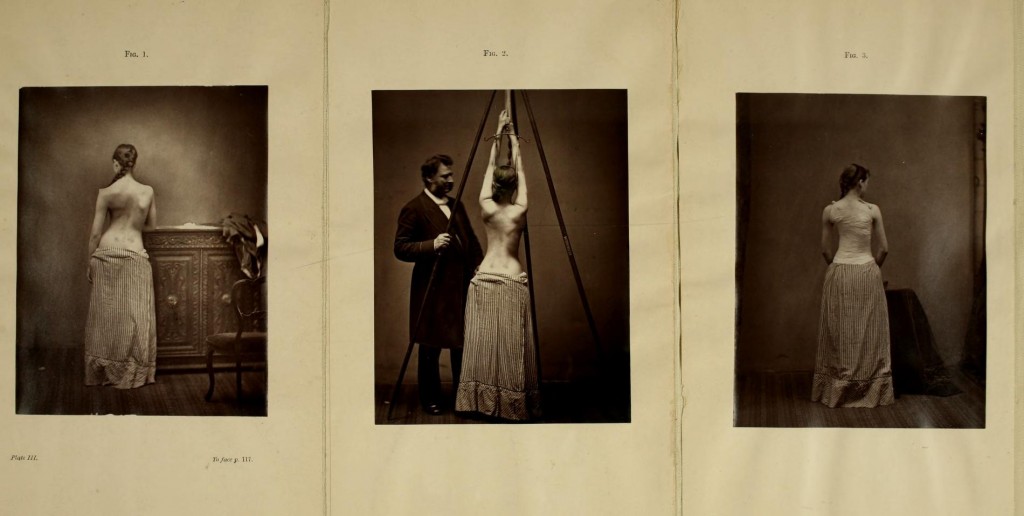

William and Linda Benitt with a Chinese guest on their farm (1931). Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society.

arrival on the farm, the couple joined their neighbors in demanding utilization of federal funds to build electric lines to farms. As a result of their efforts, electricity came to Washington County in 1938.

A year later in 1939, Linda was recruited by the educational staff of the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (A.A.A.)—an agency created in 1933 by the New Deal. The A.A.A. originally aimed to increase farm income by controlling production, but eventually shifted to authorizing crop loans and offering crop insurance on wheat threatened by drought. Linda’s role was to educate town women on farming problems and promote community dialog. Although at first reluctant to leave her farm, Linda’s dedication to the political message of the A.A.A. and concern over the increase in tenant farming eventually won her over. For the next four years she traveled statewide to organize town meetings and lead discussions on farming issues, stopping only when the program lost congressional funding in 1943.

Returning to farm life in Washington County did not suppress Linda’s dedication to activism and education. In 1945, she began a social service program for young children focused on creating a sense of personal responsibility for community life in a democracy. Linda also became involved with the Upper Midwest Women’s History Center, a regional teacher-training center that helped educators integrate women’s curriculum into regular history classes. Additionally, both Linda and William were active in local war-related efforts; in addition to participating in local blackouts, the couple volunteered to be civilian airplane spotters. In 1946, Linda received the Virginia Skelley Achievement Award, which honors leadership and work ethics.

In 1958, at the age of 67, Linda and William sold Apple Acres and spent the next four years traveling both internationally (taking a freighter trip around the world, and separate excursions to Europe and the Middle East) as well as coast-to-coast nationally, living in a little house on a truck. In 1961 the couple moved to the Penney Farms Retirement Community in Clay County, Florida. Linda died in February 1983 at the age of 92; William died a year later in 1984.

A page of the University of Minnesota’s Class of 1914 yearbook, sent by UMN’s archivist, included a portrait of a young Linda. She was described as “Suffragette, rather militant. We’d like to see you mad.” Linda was a strong woman with a passion for education and public service; her early beginnings as the first woman graduate with a certificate from Harvard University eventually led her to a long, fulfilling life and career as an academic, educator, agriculturalist, and activist.

Read Part 1: Lost and Found: the First Woman with a Harvard Credential.