How One Hospital Handled the 1918 Influenza Epidemic

Doctors at the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in Boston, MA outfitted for handling the influenza epidemic of 1918.

In 1918, no hospital, including the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital, a parent institution of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital, was spared the responsibility of caring for those afflicted by the worldwide influenza epidemic. The records of their battle with the mysterious illness endure in the BWH Archives held in the Center for the History of Medicine, Countway Library.

I say mysterious, because there was very little known about viruses or routes of contagion in the early years of the twentieth century. It would be more than a decade before the viral nature of influenza was uncovered and another quarter-century before the development of a vaccine or the widespread use of antibiotics for secondary bacterial infections. At the time, hospitals such as the Brigham could offer influenza patients supportive care (fluids, oxygen delivery, attention to heart, bowels, etc.). Also considered therapeutic—a good dose of fresh air.

Ventilation

The current Brigham and Women’s Hospital complex evolved on the site of the original Peter Bent Brigham Hospital. The Peter was designed in 1912 in the pavilion style, a hospital building system for which Florence Nightingale had been a strong advocate in the late Victorian era. The idea was that disease was probably spread in the “miasmic” air around the sick. This meant that patient wards were built as physically separated buildings designed for maximum cross-ventilation, with extra space between patients, and access to the outside. The wards were connected to each other and the main hospital building by an outdoor walkway.

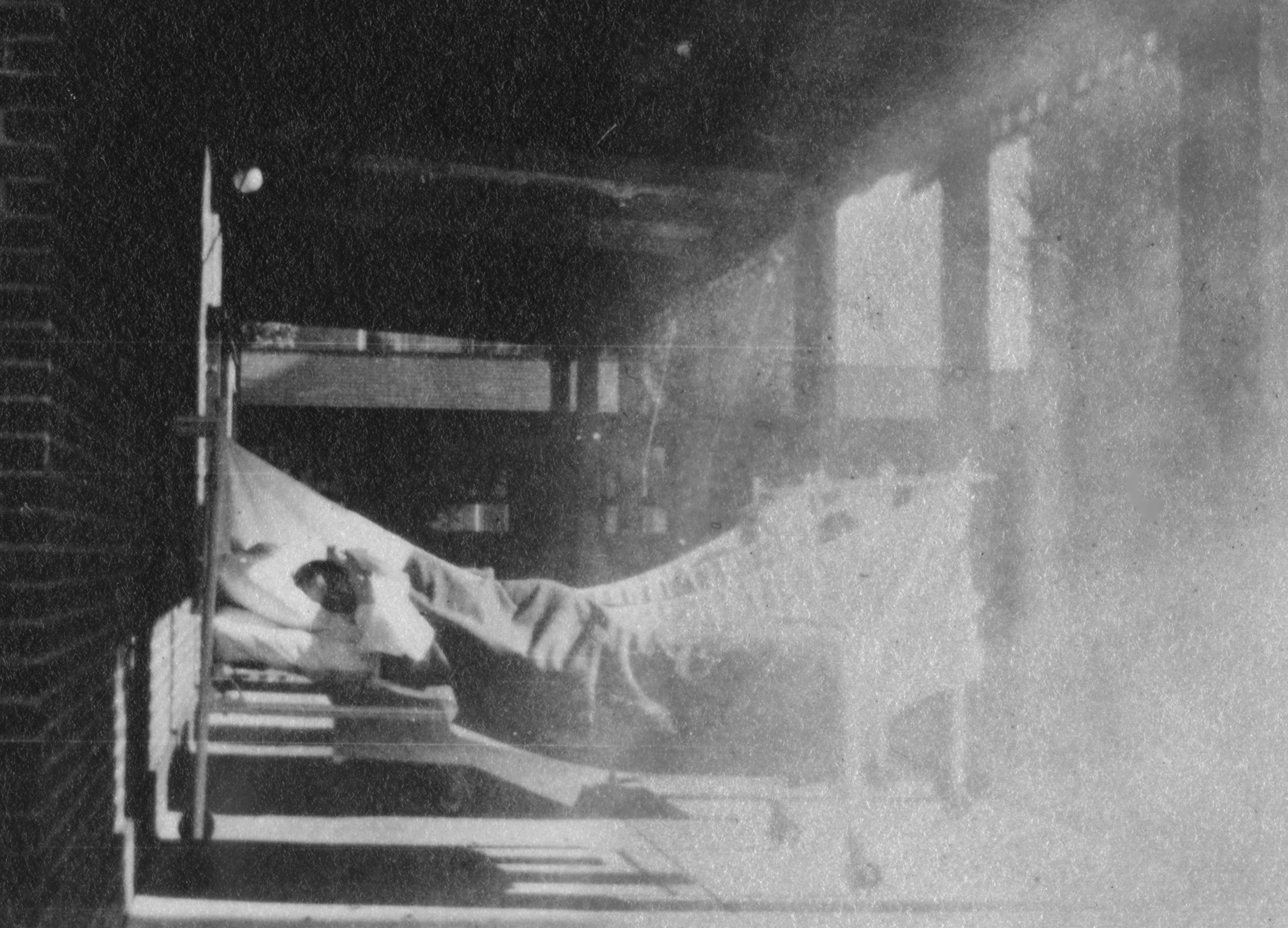

The patient wards of the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in 1918. Note the outdoor beds for flu victims. (The ward pavilions were torn down in 1980.)

Flu patients in the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital recovering outdoors on the ward porch in 1918. Many archival photographs show patients recovering from illness outside in the early years of the hospital.

A New Warfront

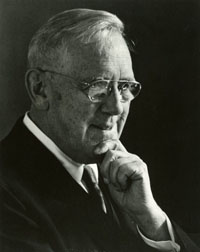

When the influenza epidemic hit Boston, Dr. Henry A. Christian, the first Physician-in-Chief of the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital, was already dealing with a shortage of the experienced doctors and nurses who had taken leave to serve at military hospitals during the first World War—the armistice coming too late in the year to cause an appreciable change in staffing. Though filled to capacity and understaffed, the Brigham’s doctors, nurses, students, and volunteers worked selflessly to help the afflicted.

The best account of how the hospital managed the unexpected avalanche of influenza patients and the toll on his staff is from Dr. Christian’s own 1918 report:

The Influenza Epidemic

In the year 1918 no hospital event exceeded in importance and seriousness the epidemic of influenza, which burst upon Boston in September, and at the close of the year, was still prevalent, though to a lessened-degree. For a number of weeks practically the entire hospital was given over to the care of influenza cases. Every medical bed and half of the surgical beds were occupied by influenza cases. In the remaining beds were concentrated such surgical and medical cases as must needs remain in the hospital or be admitted as emergency cases. The Surgical Staff loaned to the Medical four of their house officers to care for influenza cases, and very generously the surgeons curtailed their work to a minimum. Without this help from the Surgical Staff we would have been unable to meet the needs of the situation.

The hospital cooperated with the Board of Health and took, in the main, cases selected by them, patients who could not be cared for at home, or those in almost dying condition that it was necessary to get out of their homes to ease the problem of home management of less seriously sick ones. Many died in a few hours after being brought to the hospital. The wards were filled with patients extremely ill with the pneumonia that accompanied influenza. More than half of our nursing and medical staffs themselves had influenza, but we managed to carry on without any outside help and without using probationers [newly admitted student nurses] or nurses’ aids in the immediate care of patients, feeling that for the less well trained the dangers of acquiring the disease from contact was greater.

From September 9 to December 31 we treated 557 cases of influenza. Of these about 60 per cent had clinically demonstrable pneumonia, a large percent being admitted to the hospital with pneumonia already developed. Of the influenza cases 153 died. A striking contrast to the general hospital cases were our nurses and doctors, who, put at once to bed and kept there, recovered with one exception. It seems certain that failure to go to bed and remain there was an important cause of the high mortality of the disease throughout the country. It had seemed wise to us to insist on a prolonged stay in bed after the temperature was normal. The very few relapses that we saw seemed amply to justify this course. No patients were hurried out of the hospital; all were urged to stay until we felt sure that their strength made the exertion of home life and getting there safe. In following up our patients since discharge we have found that results appear to show the wisdom of this course, for bad after-effects of the disease have been surprisingly few in our patients.

In handling influenza patients all who came in contact with them were gowned, capped, and masked, and care in washing hands was insisted on. Our present knowledge of influenza is too inadequate to make certain how far these precautions are necessary. At present they seem wise. Consideration of the infection among our nurses and doctors indicates that they acquired the disease not from patients in the wards but from contact with one another, or with maids, or with outside friends just developing the disease; in other words, the disease is most contagious during the incubation period. Only one non-influenza patient in the hospital acquired the disease in the hospital wards, and one patient acquired influenza in the operating room, probably from one of the doctors who assisted in operating on him as the doctor shortly thereafter developed influenza. Thus it would seem reasonably easy to maintain quarantine, even within an infected institution, when all visitors are excluded and other means of isolation are carried out. Such rigid quarantine probably is not possible in the community at large…

…Our nurses did most excellent work during the epidemic. The numerous cases of the disease among them made it necessary for the well ones to work with redoubled energy. Pupil nurses had to replace graduate head nurses as the latter fell ill, and so had thrust upon them much responsibility. Nurses could not but feel the grave danger they ran in handling a disease which evidently in some part of its course was extremely contagious and which was causing a high toll of deaths right under their eyes. There was no faltering; each did her duty and carried out her work efficiently. Particularly did the night nurses have a strenuous time, for in the silent hours of the night delirium was most active, and then it was that death claimed its largest numbers. The way our nurses met these demands upon them has caused the staff to feel great pride in them, and has been, I am sure, an occasion for much gratification to Miss Ivers and her associates who are immediately responsible for the training of the nurses. Personally it is a pleasure to me to voice here the feeling which all of the Medical Staff shares.

Leone N. Ivers, R.N., Acting Superintendent of Nurses, reported the situation for her nurses that same year:

On September 16, 1918, twelve nurses came down with influenza, and this epidemic was very serious during the balance of the year; the blackest day starting with forty-five nurses off duty. It was necessary for about one month to increase to a ten-hour day, with one afternoon off each week and four hours on Sunday. Enough cannot be said of the faithfulness and devotion of the nurses able to continue on duty during this period. It is with sincere regret that I am obliged to record the death of two of our pupil nurses. Marion Louise Winslow died from influenza at the New York Nursery and Child’s Hospital, New York City, October 12, 1918. She would have graduated January 26, 1919. Mabel Downton died from influenza at this hospital December 28, 1918. She was just starting on her senior year.

The full reports of all the administrators of the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in 1918 can be read in the online version of the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital Annual Report for that year:

https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:427307276$1i