In 1846, Nathan Cooley Keep, a dentist, fashioned a set of false teeth for his patient George Parkman. A renewed focus was recently placed on the casts used to create these false teeth as part of an inventory project for the artifact collection of Harvard Medical Library. When he made these casts, Keep had no idea that a few years later, this work would lead to him testifying in a murder trial and giving the first piece of forensic dental evidence.

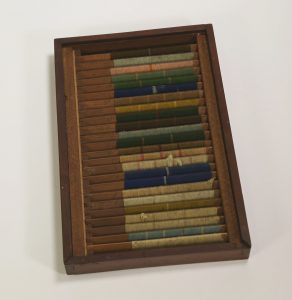

Inferior dental cast. From the Harvard Medical Library in the Center for the History of Medicine, Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine (a002.031)

George Parkman (1790-1849) was a doctor from a wealthy family and a well-known part of the Boston elite. Parkman graduated from Harvard Medical College in 1813 and traveled to Europe to continue his studies. While Parkman remained a medical philanthropist throughout his life, he turned his career to real estate and developed his fortune even further. Parkman had bought up so much land in Boston that he donated some of it to the Medical School at Harvard so that they could relocate from Cambridge to Boston. Parkman also began to lend money and was known for his long walks around the city to collect his debts as he was too thrifty to buy a horse. He was on one of these walks on November 23, 1849, when he was seen entering Harvard Medical College to speak with John Webster.

John White Webster (1793-1850) was a lecturer of chemistry and geology at Harvard Medical College. Webster was also a part of Boston high society, but his salary could not cover his expenses and his family was forced to give up their Cambridge mansion. Webster began borrowing money from a number of friends in order to deal with his financial difficulties. One of these friends was George Parkman. Webster began borrowing from Parkman in 1842 and continued to borrow large sums without paying Parkman back. By 1849 he owed Parkman so much money that he took out a loan from another friend to repay him but had used the same mineral cabinet as collateral that he had used with Parkman. The two agreed to a meeting at the Medical College on November 23, 1849, in order to come to an agreement regarding Webster’s debt. Parkman was seen entering the building at 1:45.

Later that day the janitor, Ephriam Littlefield, was surprised to find that Webster’s laboratory was locked from the inside. He could hear water running inside, although Webster was not there. Littlefield’s suspicions began to grow when news spread that Parkman, who he had seen entering the building on the 23rd, was reported missing. Prior to Parkman’s visit, Webster had asked Littlefield a number of questions regarding the dissection vault. A few days after the meeting Webster had asked Littlefield if he had seen Parkman and appeared agitated when Littlefield said he had. Webster had also given him a Thanksgiving turkey, which seemed strange to Littlefield as Webster had never given him a gift before.

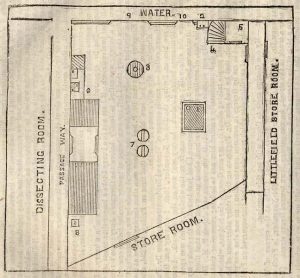

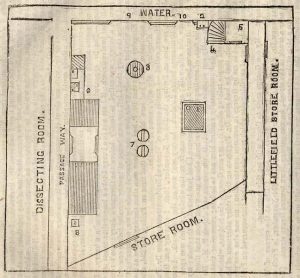

Floor plan of Webster’s laboratory from Trial of Professor John W. Webster for the Murder of Doctor George Parkman

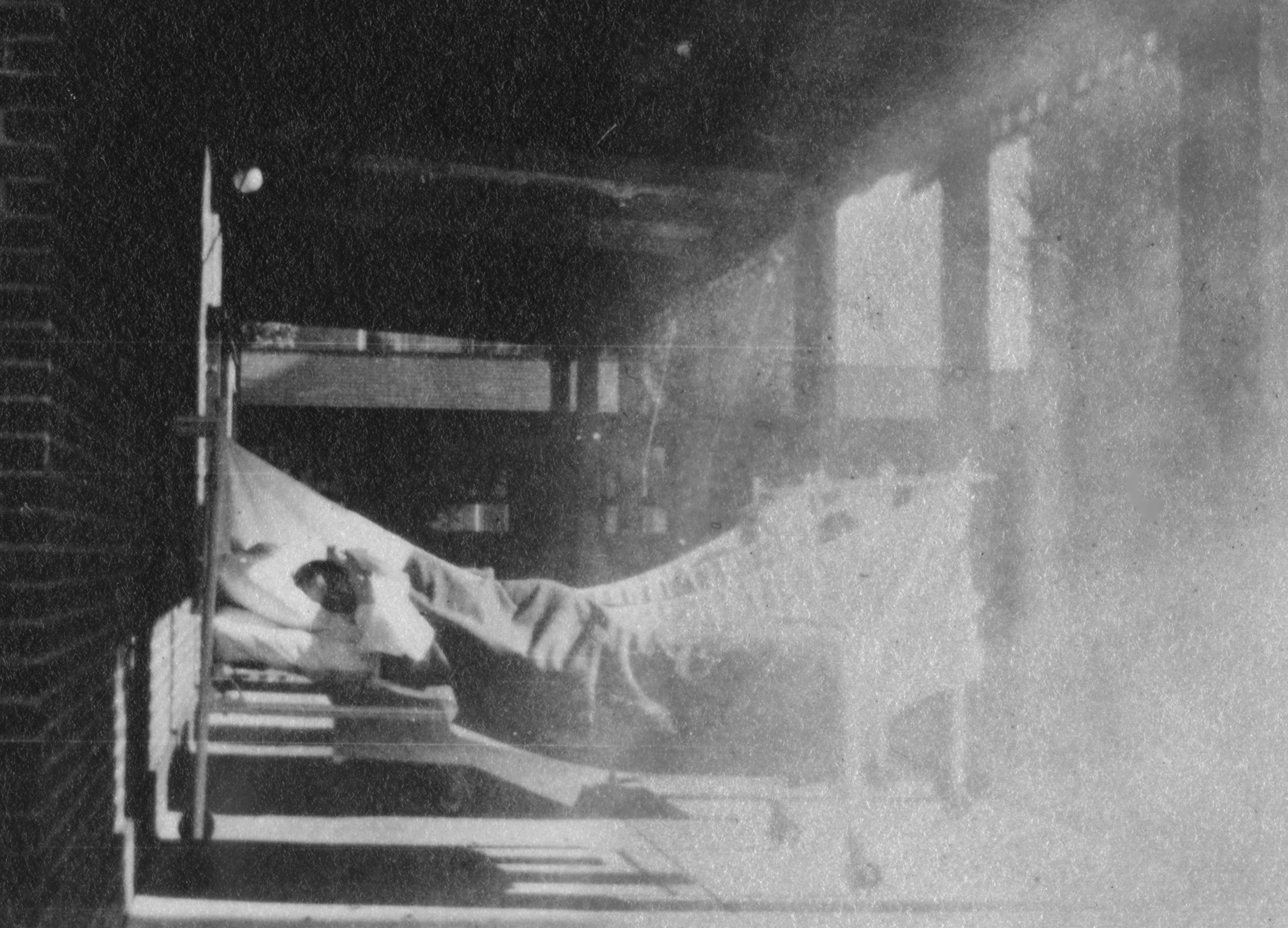

Littlefield began to watch Webster closely. On November 28, 1849, he spied on Webster through the space underneath his door and watched Webster go back and forth between the furnace and the fuel closet several times. When Webster left, Littlefield broke into the laboratory through a window. He noticed that the kindling was nearly gone and there were strange spots of what looked like acid around the room. Over the Thanksgiving break, Littlefield began to excavate the wall underneath Webster’s private privy. After two days of digging, he uncovered a foul stench and what looked like a human pelvis. He called the police, who began a search. Eventually, a human pelvis, right thigh, and left calf were found in the privy. A jawbone and teeth were found in the furnace. John White Webster was arrested and put on trial for the murder of George Parkman.

Because Parkman was such a well-known figure, the public was already obsessed with the case by the time of Webster’s arrest. When they learned the details of the charges against Webster, the case became even more salacious. Not only had Parkman been killed by another doctor, but he had also been dismembered and the pieces of his body had been hidden in the medical school. Newspaper headlines all revolved around Parkman and Webster, and tickets to the trials were so popular that spectators were being allowed in for a short time and then ushered out to make room for newcomers. It is estimated that thousands of people witnessed at least part of the trial.

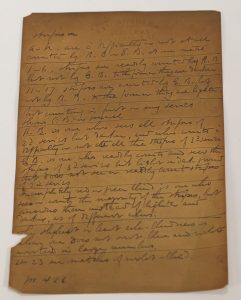

Because of the state in which the remains were found, the prosecution had to prove that the body was, in fact, that of George Parkman and that his death was a result of homicide. Multiple witnesses were called to the stand to confirm the identity of the body and the manner of death. Many of these people were Webster’s colleagues from the Medical College, including Jeffries Wyman (1814-1874), who testified that the remains matched the height and general size of Parkman, and Oliver Wendell Holmes (1809-1894), who testified that a small wound on the chest could have been a fatal stab wound. Ephriam Littlefield also testified, describing the events of the days leading up to and following Parkman’s disappearance.

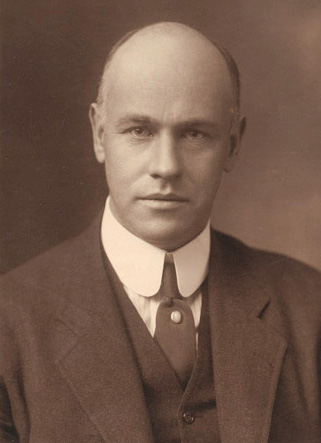

One of the most important pieces of testimony came from Parkman’s dentist, Nathan Cooley Keep (1800-1875). Keep, who later became the founding dean of the Harvard School of Dental Medicine, was a prominent dentist with high aspirations to unite dental and medical education at the time of the trial. He testified that the jawbone found in the furnace contained false teeth that he had made specifically for Parkman. Keep then showed the jury that the jawbone from the furnace fit perfectly into the plaster impression he had created of Parkman’s jaw in 1846 when he was fitting Parkman for the false teeth. Keep also showed them that loose teeth found in the furnace fit into the plates he had created. This convinced the jury that the body found in Webster’s laboratory was indeed George Parkman.

Bottom of superior dental cast showing Dr. Parkman’s name. From the Harvard Harvard Medical Library in the Center for the History of Medicine, Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine (a002.031)

John White Webster was found guilty of the murder of George Parkman on March 30, 1850, and was sentenced to be hanged. Although some still doubt his guilt, Webster confessed to the murder in June of 1850 and was executed on August 30, 1850.

Although the case was famous at the time for its association with Boston high society, there is another reason that the trial of John Webster has lived on. This was the first time that dental evidence was accepted as part of a murder trial. These plaster casts were a vital part of the prosecution’s case, as they were the only piece of evidence or testimony that could confirm without a doubt that the body Littlefield had found was George Parkman’s. Over a century and a half after Keep introduced these plaster casts into evidence, dental evidence has become a key part of forensic science. Dental records are used to confirm identity today in much the same way that Keep used his plaster casts. The field has expanded over time, and when matching dental records cannot be found, teeth can be used to estimate identifying traits such as age and ancestry. George Parkman was the first person to be identified through forensic dentistry, but he was far from the last.

The Parkman-Webster case was not only a media sensation. It was a landmark case in the history of forensic medicine.