Peter Bent Brigham Hospital Records Opened for Research

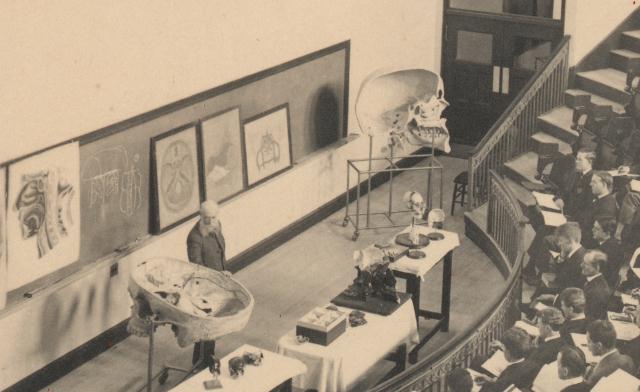

First staff with Sir William Osler at dedication of the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital, April 30, 1913.

The Center for the History of Medicine and the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Medical Library are pleased to announce that the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital Records, 1830– (inclusive), 1911–1980 (bulk) are now formally open for research. A guide to the collection can be read via this link: http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HMS.Count:med00057

The collection of historic material related to the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital (PBBH), one of the parent hospitals of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital, includes photographs, memorabilia, business records, and historic publications that were created before its merger with Boston Hospital for Women and Robert B. Brigham Hospital in 1975, and while it operated as a division of the Affiliated Hospitals Center (AHC) until 1980. (In 1980 the three AHC divisions were moved into the same new facility and unified under the new name, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, a teaching affiliate of Harvard Medical School.)

The Peter Bent Brigham Hospital collection includes much of its early administrative data, going back as far as 1902, when the corporation to construct the hospital was formed and its close relationship with Harvard Medical School began. All of the hospital’s Annual Reports (1913–1979), Executive Committee Meeting Minutes (1912–1980), and Board of Trustees meeting records (1902–1975) tell the story of the growth of a major metropolitan hospital from its opening in 1913 through the development of modern medicine during the greater part of the 20th century. The collection also includes records of the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital School of Nursing (1912–1985), which became one of the preeminent training programs for nurses in the United States. Other hospital publications codify hospital procedures and standards over time, and the newsletter, Brigham Bulletin, adds depth to the hospital’s biography with weekly, more personal stories about the individuals and events that made the organization unique.

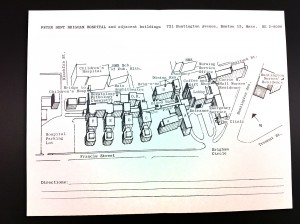

The collection includes 1911 construction records for the original 225-bed, pavilion-style hospital built along Francis Street in Boston, as well as for later additions.

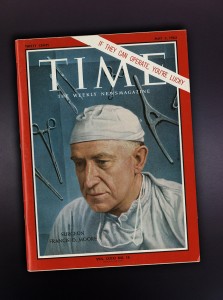

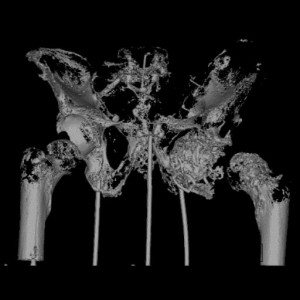

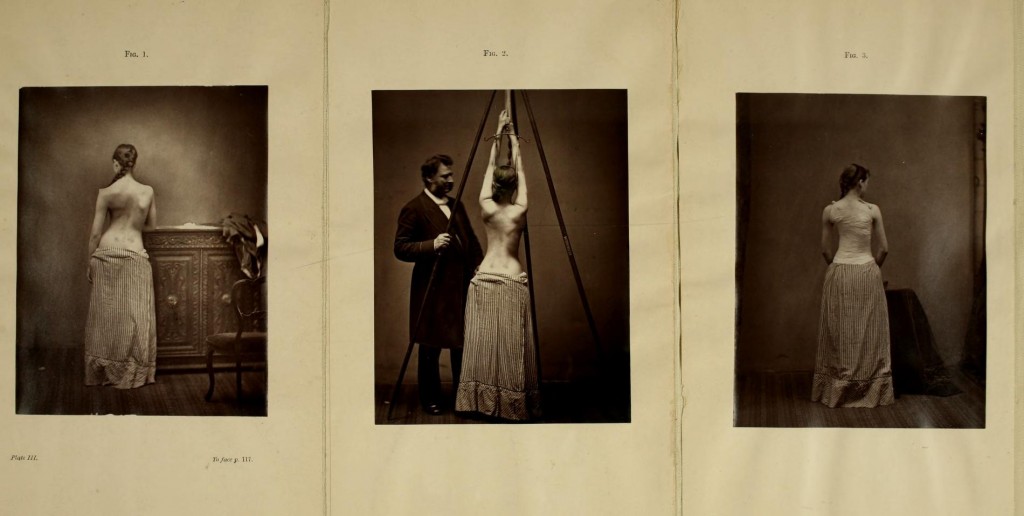

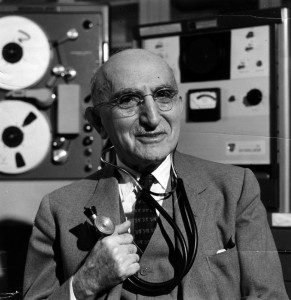

Photographs comprise the largest portion of the collection and provide thousands of images of hospital, staff, and activities from 1911–1980. The archival collection includes images of some of the individuals whose work at the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital significantly advanced medical science and education, including: Dr. Francis Moore, considered the “father of modern surgery;” Dr. Harvey Cushing, first PBBH Surgeon-in-Chief, an innovator in neurosurgery; Dr. Samuel A. Levine, a key figure in modern cardiology; Nurse Carrie M. Hall, a leader in the evolution of professional nursing education; Dr. (Brigadier General) Elliott C. Cutler, second PBBH Surgeon-in-Chief and Surgeon-in-Charge of the European Theater of Operations during WWII; Dr. Carl Walter, who developed a way to collect, store, and transfuse blood; and Dr. Joseph E. Murray, the 1990 co-recipient of the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine. He, along with his team of PBBH medical pioneers achieved the first successful kidney transplant in 1954.

Many interesting hospital related artifacts are part of the collection. A menu and china from founder Peter Bent Brigham’s restaurant, a World War I service flag and many of Nurse Carrie Hall’s service medals from the same war; mid-century nurse’s uniforms, caps, and capes; scrapbooks, audio recordings, newspaper clippings, old medical instruments, student notebooks from the nursing school, and the contents of the PBBH 1963 time capsule are some of the widely various objects that can be found here.

The Peter Bent Brigham Hospital Records, 1830– (inclusive), 1911–1980 (bulk) is the last of the major collections of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Archives to be cataloged and opened to the public for historic research. The online finding aid to Peter Bent Brigham Hospital Records joins those for the other parent hospitals of the Brigham and Women’s, including the Boston Lying-in Hospital Records, 1855–1983 (Bulk 1921–1966), Free Hospital for Women Records, 1875–1975, Robert B. Brigham Hospital Records, 1889–1984 (Bulk 1915–1980), and the Affiliated Hospitals Center (Boston, Mass.) Records, 1966–1984. To view those online collection guides as well as the guide to the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Records, 1900– go to this page: https://www.countway.harvard.edu/chom/brigham-and-womens-hospital-archives

![Pocket field surgery kit, used in the American Civil War and found on a battlefield in 1862, Warren Anatomical Museum [WAM 21049], Francis A Countway Library of Medicine](https://cms.www.countway.harvard.edu/wp/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/21049_v1.jpg)

![Eli Lilly box containing Liver Extract #343, dated 1929. Warren Anatomical Museum [WAM 21053], Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine](https://cms.www.countway.harvard.edu/wp/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/21053_v1.jpg)