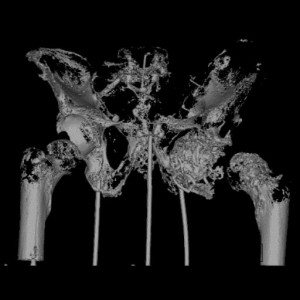

Specimens on display for Anatomy Day, 2016.

From roughly the 1840’s through the 1940’s, the Warren Anatomical Museum (WAM) collected and acquired several hundred anatomical wet tissue specimens from medical institutions and from area physicians and academics. While these specimens were originally on display within the museum, the relocation of the WAM to a smaller venue prompted the move of these specimens into storage. In April of 2015, the Museum Collections Technician, Alex Denning, began the task of cataloguing and documenting these specimens. As is the nature with any biological material, the condition of many of the specimens has deteriorated over time, despite preservation efforts. Throughout the history of collecting and saving specimens, chemical preservatives, such as ethanol (or other alcohols and ‘spirits’), formalin and formaldehyde, and various other chemical combinations, have been used to fix (render inert and stable) and preserve anatomical tissues. There is great variability in the current conditions of these specimens and they vary in subject matter from gross anatomical dissection specimens used in teaching, to pathological specimens retained for educational purposes due to their rarity.

Clavicle with sarcoma.

The task of moving over 800 specimens from museum storage to a laboratory space presented a number of logistical challenges. Due to the nature of the specimens, being housed in a variety of potentially unknown chemical preservatives, relocation of hundreds of medical specimens proves difficult and must be undertaken by special transport. Specimens were properly secured into containers and transported in specialized vehicles to make the journey to the lab. The specimens are now being processed in batches, the first of which contains 300 specimens and is nearing completion.

Processing a historic specimen involves identification, photographing, data collection, cleaning, and repackaging. Each specimen corresponds to a museum number that (hopefully) has documentation on the origins of that particular specimen. Over time, many paper labels have been lost and few specimens have their museum number etched into the glass container or on a tag within the container. This makes identification difficult and many specimens will receive temporary ID numbers until they can be identified through the process of elimination. Within the wealth of information available at WAM and the Center for the History of Medicine (CHoM), often there will be donation or loan histories, and sometimes even patient and surgery information that help to provide context for a particular specimen.

The most important and time-consuming step for each specimen is the data collection. Condition notes are collected, which note the fluid levels and coloration, any deterioration of the specimen, and stability of the container and its seal. Photo documentation is also a vital step in this process as it records the condition and appearance of a specimen in its found state, which also serves as important data for future processing of specimens. Once documentation is complete, the exterior of the specimen container is cleaned, small cracks are sealed or stabilized, and if possible, a fluid sample is collected for future identification. The specimens are then repacked safely and returned to their storage containers.

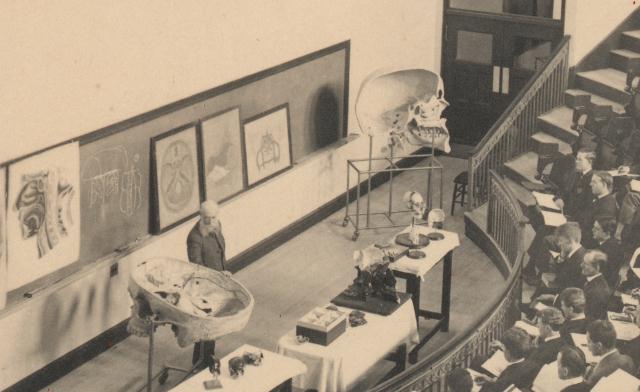

Dr. A. T. Hertig, Dept. of Pathology, HMS, using specimens to teach medical students.

As soon as a specimen is fully documented, all data, photographs, and archival information are entered into the WAM database. Efforts are currently underway to make this information available to researchers and the medical community in the future. The project has sought the help of a number of anatomists, pathologists, and medical historians to assess the potential of each specimen for teaching and research purposes. The goal of this project is not just to document and conserve existing specimens, but it is also the hope of the WAM to eventually open specimens up to researchers and scholars upon the project’s completion.

![Phrenology cast of Eustache Belin, Warren Anatomical Museum, Francis. A. Countway Library [WAM 03235]](https://cms.www.countway.harvard.edu/wp/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/03235_v1.jpg)

![Pocket field surgery kit, used in the American Civil War and found on a battlefield in 1862, Warren Anatomical Museum [WAM 21049], Francis A Countway Library of Medicine](https://cms.www.countway.harvard.edu/wp/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/21049_v1.jpg)

![Eli Lilly box containing Liver Extract #343, dated 1929. Warren Anatomical Museum [WAM 21053], Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine](https://cms.www.countway.harvard.edu/wp/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/21053_v1.jpg)