Checking in from the field: Donna Drucker

Guest Blogger Donna J. Drucker, MLS, PhD, Technische Universität Darmstadt, 2018–2019 New England Research Fellowship Consortium Fellow

“Advertising Contraception in the 1970s and Beyond”

Before the legalization of the hormonal pill, advertising of contraceptive methods to U.S. women in the 1930s and 1940s left much to the imagination. Even after the Supreme Court legalized the use of contraception as prescribed by physicians in November 1936, manufacturers mostly depicted the hands and arms of women preparing spermicides and diaphragms (http://www.technologystories.org/materializing-gender-through-contraceptive-technology-in-the-united-states-1930s-1940s/). At most, the instructional packaging would show a sketch of hands placing a diaphragm or spermicide applicator inside the woman’s body. Did the tone of advertising change after the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the pill for contraceptive use in June 1960? Looking at examples available in the Countway Library of Medicine’s collections shows that manufacturers continued to advertise only to a limited group of women for decades afterward.

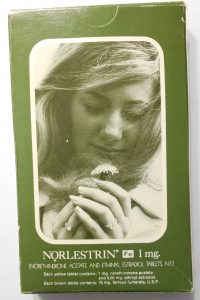

One example is the image used on a September 1970 flyer for Parke, Davis’s hormonal pill, Norlestrin.

The instructional booklet contained no images of women’s bodies, only images of women’s heads and hands with wedding rings prominently displayed. The woman on the front cover looks thoughtfully at a dandelion in her hands. When the FDA first approved the pill, its approval extended only to married women, and the instructional packaging reflected the company’s consciousness of that fact. Doctors could legally prescribe the pill only to married women until March 1972, when the U.S. Supreme Court’s Eisenstadt v. Baird decision extended the right to privacy to unmarried people.

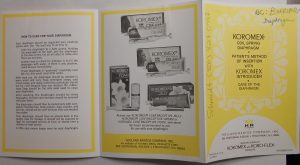

That conservative streak in advertising continued in commercial contraceptive product advertising long after Eisenstadt. The Boston Women’s Health Book Collective (BWHBC) Subject Files contain multiple examples of such contraceptive advertising from the late 1970s through the mid-2000s. One of those was in a November 1979 instructional flyer for a Koromex diaphragm.

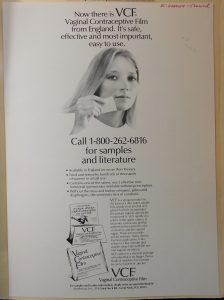

The flyer advertised the spermicidal jellies, creams, and foams that the Holland-Rantos Company recommended women use with the diaphragm. Two of the spermicide packages showed a young, white, blond woman smiling, and two others showed daffodils. A second late-1970s example was for VCF spermicidal film, known in the United Kingdom as C-Film, also depicted the head and hand of a young, white, blond woman. She holds a package of the film with a serious expression, but the film itself is not visible.

While spermicides are still available in the U.S. and are marketed for use with barrier methods, they never caught on as methods to use alone.

The last example from the BWHBC Subject Files is an empty package for a product called the Bikini Condom, which appears to have been designed by an Emory University professor of obstetrics and gynecology called Robert A. Hatcher in 1990–1991. In a letter to the company International Prophylactics, Inc. (IPI), Hatcher claimed that “it empowers women,” and that “it has a good future as a contraceptive.”

The package has two images: one of a smiling white brunette woman looking off into the distance and another of the bikini condom itself. IPI briefly manufactured it, but it never seems to have caught on more widely.

By examining these examples of contraceptive advertising for women, it seems that manufacturers only envisioned white, middle-class, well-groomed women using their products. Of course, contraception was a concern of anyone desiring to prevent a pregnancy and engaging in behavior where sperm and egg could meet, but neither major nor minor manufacturers included broader representations of potential customers on their packaging.

Donna may be based in Germany, but check into what she is working on via Twitter @histofsex