Oliver Wendell Holmes’ Friendship Cup

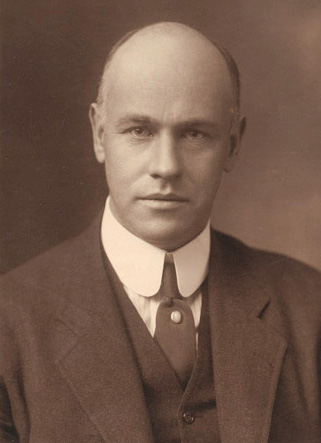

On August 29, 1889, former dean of Harvard Medical School Oliver Wendell Holmes (1809-1894) turned 80 years old. Annie Fields (1834-1915) and Sarah Orne Jewett (1849-1909), along with nine other women, presented Holmes with this silver loving cup at his birthday celebration. The cup entered the Harvard Medical Library collection in 1940 when Mrs. Richard Rule—the great-granddaughter of Holmes’ sister—presented it to the Department of Anatomy. A renewed focus was recently placed on the cup as part of an inventory project for this collection.

Oliver Wendell Holmes Friendship Cup. From the Harvard Medical Library in the Center for the History of Medicine, Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine (a001.098)

Holmes was the Dean of Harvard Medical School from 1847-1853 and was the Parkman Professor of Anatomy and Physiology until he retired in 1882. Holmes was a skilled physician who made great contributions to research in puerperal fever and was the first person to bring a microscope into an anatomy classroom in the United States. Along with his medical prowess, Holmes was also a prolific writer. He published both poetry and prose. He came up with the name for the magazine The Atlantic and contributed to it many times. These worlds often collided for Holmes: much of his writing revolved around the medical world, and he frequently gave recitations of his poetry at events for medical institutions.

The 1889 loving cup—called the “Friendship Cup”—is engraved with a quote from Holmes’ poem “The Sentiment”. The engraving reads:

The Pledge of Friendship

Tis the heart’s current lends the cup its glow

Whate’er the fountain whence the draught may flow

A loving cup is a shared drinking vessel and is usually used at weddings and other celebrations. In the 19th century, they were popular for trophies and commemorative gifts. Holmes was particularly enamored with the design of the cup. The names of the donors were on the bottom. In theory, the names could not be seen if the cup was full, so it would have to be emptied—and therefor shared—before they could be read. He highlighted this aspect of the cup in his poem, “To The Eleven Ladies Who Presented a Loving Cup to Me”, which begins:

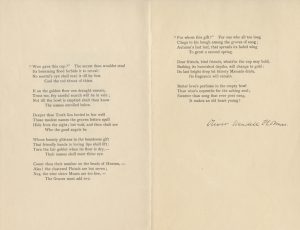

“Who gave this cup?” The secret thou wouldst steal

Its brimming flood forbids it to reveal:

No mortal’s eye shall read it till he first

Cool the red throat of thirst.

If on the golden floor one draught remain,

Trust me, thy careful search will be in vain;

Not till the bowl is emptied shalt thou know

The names enrolled below.

Originally, only twelve copies of this poem were printed: one for Holmes and one for each of the donors. He signed these copies by hand. Holmes later published the poem in his 1891 book Over the Teacups, a collection of poems and essays centered around fictional breakfast-table conversations.

One of Twelve Original Copies of “To The Eleven Ladies”, signed by Oliver Wendell Holmes. From the Boston Medical Library in the Center for the History of Medicine, Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine.

Not much is known about the donors or why they presented Holmes with this gift, but there are a few notable names on the bottom of the cup. Annie Fields was a writer who published collections of poetry and essays as well as biographies of notable literary figures. Her husband, James Fields, was a publisher. Together they ran literally salons out of their home, many of which were attended by Holmes. Annie Fields was also the sister of Zabdiel Boylston Adams, Jr., who was a surgeon and attended Harvard Medical School while Holmes was Dean. Sarah Orne Jewett was a friend and later companion of Annie Fields. She was also a writer and was best known for her work describing rural New England Life. Her father, Theodore Herman Jewett, was a doctor. Her experience accompanying him on his rounds as a child inspired her book A Country Doctor.

It is easy to see why Fields and Jewett would have been drawn to Holmes, and although not much is known about the other donors, the Friendship Cup is a clear sign of admiration from all eleven women. Holmes’ poem indicates that the admiration was reciprocal. This reciprocity is part of what makes the Friendship Cup stand out in the collection: it doesn’t just reveal information about Holmes himself, but about his friendship with the donors. Although this loving cup was donated to the Harvard Medical Library as an artifact relating to Oliver Wendell Holmes, it sheds some light on the lives of eleven others as well.